Never "there", always elsewhere or elsewhen

The phrase “forever elsewhere”, coined by MIT professor Sherry Turkle, doesn’t just describe a cultural shift—it captures the neurological cost of growing up in a state of continuous distraction.

For adolescents, whose brains are undergoing critical developmental changes, this constant split in attention is not benign. It reshapes emotional regulation, social processing, and the capacity for deep focus—often in subtle but lasting ways.

Jonathan Haidt, in his book The Anxious Generation, highlights how the smartphone revolution collided with the most plastic and vulnerable stage of brain development: adolescence. The result was not just cultural change, but cognitive transformation.

“Always elsewhere” became normalized in the post-2010 digital world, and Gen Z—caught mid-brain-rewiring—is paying the highest price.

The Acceleration: How 2010–2015 Changed Everything

Between 2010 and 2015, a sharp and simultaneous rise occurred across multiple indicators of adolescent digital life and vulnerability. Jonathan Haidt refers to this period as “The Great Rewiring of Childhood”. It wasn’t just a technological shift—it was a psychosocial transformation unfolding in real time.

During this short window:

- Self-harm among teenage girls began rising rapidly, after decades of stability.

- Depression and anxiety rates surged, particularly among preteen and teen girls.

- Smartphone ownership jumped from minority to majority among adolescents.

- Social media use, especially Instagram, shifted from optional hobby to social necessity.

These changes did not occur gradually. They were stacked and synchronized—amplified by a perfect storm of hardware, software, and cultural acceptance. At the heart of it was a convergence of technologies that redefined how young people related to each other—and to themselves.

For teens, the phone was no longer just a communication tool. It became a mirror, a stage, and a sensor constantly attuned to peer approval.

According to the Pew Research Center, smartphone ownership among U.S. teens rose from 73% in 2015 to 95% by 2022 (Pew Research: Teens, Social Media and Technology).

Even children aged 8–12 reached significant levels of smartphone access before reaching high school.

This steep rise marks a generational divide: Gen Z was the first to experience adolescence almost entirely mediated through mobile connectivity and algorithmic social comparison.

Social Media Adoption Reached Adolescents Faster Than Any Prior Technology

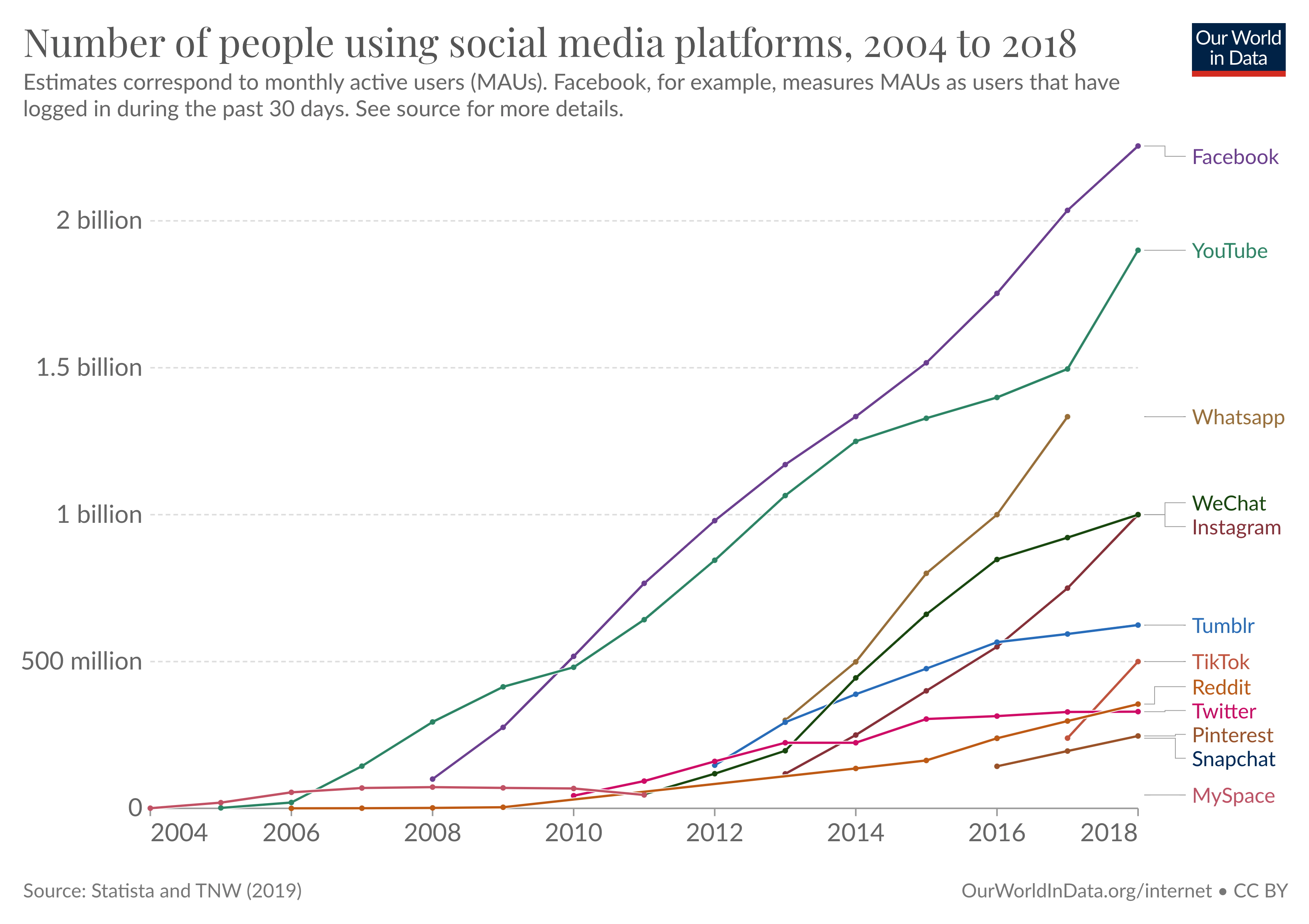

The rise of social media wasn’t just part of a general trend toward digital communication—it followed its own steep trajectory. Starting in the early 2010s, platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram saw rapid and widespread adoption, particularly among adolescents.

true

true

Esteban Ortiz-Ospina (2019) - "The rise of social media" Published online at OurWorldInData.org.

Our world in data

- Between 2010 and 2016, Facebook and YouTube gained over a billion new users each.

- Instagram, introduced in 2010, reached 1 billion monthly active users by 2018.

- Other platforms like Snapchat, WhatsApp, and WeChat followed similarly steep growth curves—especially among younger users.

This rapid uptake happened just as Gen Z entered adolescence. For them, social media wasn’t a new tool to adopt—it was the default environment in which connection, identity, and comparison occurred. Unlike previous forms of communication technology, social media introduced continuous feedback loops—notifications, likes, follows, and comments—that shaped attention and emotional response in real time.

The Numbers Behind Our Absence

Media use statistics reflect the behavioral consequences of this technological shift:

- In 2015, teens spent an average of 7 hours a day on screen-based leisure (excluding homework).

- By 2022, 46% of teens said they were online “almost constantly” (Pew Research Fact Sheet).

- Many reported mental preoccupation with digital activity even when their devices were idle.

While teens are the most affected, this pattern of fractured attention is not unique to them. Adults, too, increasingly live in a state of partial presence. A 2023 analysis by RescueTime found that the average user checks their phone 58 times a day, with over 3 hours of daily active use, often in short, compulsive bursts.

The human mind — regardless of age — is poorly suited for constant context switching. But for adolescents, whose cognitive systems are still developing, the cost is likely far greater.

The New Normal: Half Present

Much of this behavior is invisible or socially accepted. A quick glance at a phone or a reply during conversation no longer signals disrespect—it’s routine. But these moments of divided attention erode the depth and quality of shared experience.

We now live with:

- Partial presence: Split focus between digital updates and real-time interaction.

- Deferred response: Repeatedly asking others to repeat themselves due to drifting attention.

- Social thinning: Surface-level exchanges dominate; uninterrupted dialogue is rare.

These subtle shifts are reshaping social expectations—and the adolescent brain absorbs them as normal.

Correlation or Causation?

... this is the question. Many signs suggest that social media plus "always on" are a causal factor behind the phenomena described above. But we’ll explore that in a future post.

Presence as a Scarcity

Being fully present has become a deliberate act. As distractions multiply, so too does the effort required to remain mentally in the room.

Luckily, cultural responses have emerged:

- Device-free camps for kids.

- Device-free classrooms.

- Phone-free dining zones in restaurants.

- Focus apps designed to block distractions.

These efforts underscore a growing awareness: attention is a limited and valuable resource. And for Gen Z, it may be a skill that must be actively learned or reclaimed.

Conclusion: A Generation Influenced by Distraction

“Forever elsewhere” is no longer a metaphor. It’s a developmental environment.

For a generation whose brains are still under construction, the loss of sustained attention, face-to-face interaction, and unstructured play comes at a cost. While Sthe psychological fallout is real—and will be discussed separately—the groundwork is neurological.

To reclaim presence is not just to resist distraction. It’s to shape how young minds are built.